- Home

- Shabri Prasad Singh

Borderline Page 2

Borderline Read online

Page 2

According to Papa, everything is fair in love and war. When I was a teenager, he told me that he would let me marry out of choice, the way he married my mother. Only time would tell what would happen but right then, I did not doubt for a minute that he would cheer me on as I walked into the orange sunset with the man of my dreams.

My mother was eleven years younger than him. They both had strong personalities and burning tempers. In time, my parents’ sweet disagreements would metamorphose into a marital crisis, sweeping away everything in its path.

Even mismatched relationships work for a brief while, when the participants find some common ground. For my parents, that fuzzy period flew past quickly; they never really understood each other. If there was love there, it was trampled over by ego. Like a gently plucked flower, it was beautiful, but not really alive. I sometimes ask myself which of the two was more hurt by their marriage, but like all domestic tragedies, both partners were equally mauled by their strained relationship.

A few years into his job, Papa took a deputation and began working for the Indian Intelligence, RAW. We moved from Punjab to New Delhi. His good work received notice quickly. After just a year at the desk, he was posted to the Indian High Commission in London. He was very happy.

My mother was a little unsure, but she did what she had to do and packed, and we all moved to London. I was only five and my sister, seven. My mother was, at this time, very distraught over her father’s wrongful killing. The drastic change that was about to come into our lives didn’t make the situation any better for her.

Our would-be house in London was not ready yet, so we stayed at a beautiful hotel for the first few weeks. It was there in the plush, ornate hotel room styled as a state room from the Buckingham Palace itself that Papa and Mamma sat me and my sister down. ‘From now on, Bungua (that’s what he called me), your name is Amrita Sinha and Sungua (my sister), your name is Sati Sinha.’ My sister and I laughed, and we asked Papa, ‘What is yours and Mamma’s name then?’

‘My name is Karna Sinha from now on and Mamma’s name is the same.’

‘Why is Mamma’s name the same?’ I asked. My mother never used either her father’s or Papa’s last name; she was always simply, Neelkamal.

Sati got a little serious and asked Papa, ‘Your name is R. S. Srivastava, my name is Sati Srivastava and her name is Amrita Srivastava.’ Clearly, Sati and I were confused.

‘Now the names have changed. Can you keep this secret?’

Thus challenged, I said ‘Yes, Papa.’ Sati nodded, too, and I realised this was happening because Papa was a spy.

Soon, we moved to an official house in Victoria, London. We were surrounded by other Indian diplomats, so familiarity beckoned in the midst of a new country and its strange culture.

Our first few days at school were very difficult. We were not accustomed to the language, the people, and the surroundings. On my first day, I found myself asking the boy in front of me questions in Hindi. He looked at me blankly and turned away. But like all children everywhere, we were sponges, and were speaking fluent English in no time, almost as if we were born English speakers. We even picked up a heavy accent within six months.

We had settled down and actually started liking the place. It felt as if we belonged there. My mother, too, became a part of it after doing a course in Montessori, and taking up a job as a teacher in a playschool. Relatives from India would visit us, and we would take them sightseeing. My father made some local friends, too.

The strange became familiar. The sights, sounds, smells and dampness of England seeped into my bones. Soon, we were desperate to travel. Papa wanted to see all of Europe. So at every opportunity we got, we would pack our things and take the hovercraft to Calais, from where we would drive around, seeing the magnificent sights of France, Italy, Switzerland and Germany. Every weekend and every long holiday was spent in Europe, imbibing new cultures. I don’t remember either the architectural details of the Eiffel Tower and the Louvre, nor the roads on which we drove to get there. All I remember is that we seemed the most perfect family on the planet, floating around in a dream world. Those journeys kindled a wanderlust in me that’s never been quite extinguished. I still crave to travel to distant lands, but am prevented from doing so by the tangled mass that I have become.

In Rome, we visited the Vatican and St Peter’s Basilica. We arrived completely unprepared, with no bookings or plans. My Papa had an unshakeable belief in solutions presenting themselves spontaneously. Sure enough, some nuns helped us and gave us Spartan but comfortable accommodation in a church near St Peter’s square, which also served as a bed and breakfast for tourists. I remember waking up and enjoying the delicious chocolate milk the nuns made for breakfast. We saw the Pope from his balcony, amidst a crowd of people who were exhilarated by the sight. I did not know then that this was a big deal.

I remember being mesmerised by the buildings and cathedrals I saw in these countries. In my mind, they are no longer separate journeys; they have fused into one long, meandering trek across Europe. Now I go back to those memories when I’m in a dark place, and feeling grateful for the wonderful times I’ve had, I immediately cheer up.

I was a very difficult and peculiar child. I realise this in retrospect, after years of counselling and reading up on psychology. My sister and I were very different. She was an obedient child, and, therefore, I felt she received more love than I did from my mother. But I was always my father’s favourite, no matter what! However, I did not value it so much as a child. I was determined to be my mother’s favourite as well.

Since childhood, I felt the need to prove myself. I would exaggerate stories in order to amuse people, and to become the centre of attention. At times, this habit of mine made things difficult for the family. For instance, when the rest of the family wanted to eat pizza, I would insist on eating Indian food. And after the Indian food was prepared for me, I would eat the pizza. I unintentionally made myself into a problem child. Papa never seemed to mind, but it definitely irritated my mother.

I was different: While on the surface, I was very friendly and bubbly, deep down, I struggled. When I saw children playing together in groups, I hesitated to join them as I felt out of place. I would rather play alone.

Though I was a happy child, I gradually became aggressive. I started getting into fights with my classmates on flimsy pretexts. Anger and envy became traits of my personality. I would compete with other girls by sneaking into my mother’s room and putting on her make-up.

My first crush, Alex the Cute, was a fair-skinned boy, who set the tone for my subsequent taste in men. He had blonde hair and blue eyes. Alex was actually a mix of Indian and British blood; while his father was Indian (the then High Commissioner of India in England), his mother was from the British royal family. His real name was Bhaarat Ohri.

Alex a.k.a. Bhaarat was interested in the best looking girl in class, Melissa. I was jealous of her, and craved for Alex’s attention. When we were going for a school picnic, I decided to wear a pair of denim shorts with black stockings so that Alex would notice me. However, when I was leaving the house, Papa said, ‘Bungua, you cannot wear this; go and change into something decent.’ I was miserable, yet I had no choice but to change. So I snuck the pair of stockings in my lunchbox and took them to the picnic, where I changed into those. However, Alex did not even glance at me. This was the first of my many wardrobe misadventures to ensnare the men I wanted. Now, of course, I laugh about it.

Alex’s rejection of me seemed to set a pattern. There were many men who I wanted to be with, but they had no interest in me. It was something of a curse.

I was fascinated by kissing. I had seen people do it on television. I used to make my Barbie dolls kiss the male doll, Ken. One day, my mother saw this and told Papa about it. Thankfully, he just laughed it off. I remember kissing a tree at school during breaks. Obviously, I was in my own world and assumed that no one would notice, but I was wrong. My games teacher asked: ‘Why are you kissing the tree?

’ My answer was that I was practicing kissing. I had no answer for her next question: ‘Who are you practicing for?’

I was becoming sexually aware, and my expanding consciousness began to manifest itself. My classmates Tara, Amy and I would sneak to the loo in the middle of our lunch break, and in an attempt to indulge our curiosity about what ‘it’ would feel like, we would rub our bodies against each other’s. It was a pleasurable feeling, even though I didn’t know what sex was or that what I was doing was considered to be a sexual act. Also, the act itself did not define my sexual orientation.

I was also a very brave child. Once on a school trip, I went to a glass blowing factory. With my allowance, I bought for my mother a glass duck, which was in one of my mother’s favourite colours: Stunning orange. When we got back to school, it was raining. I waited for my mother to come and pick me up, but patience was never one of my strongest virtues. So I left school without a parent or guardian and walked all the way home, alone. The fear of being scolded by parents and teachers, and being possibly punished, was overridden by the thought of how happy my mother would be to get her glass duck. Encountering strangers on the road also did not scare me; I was only seven, but a brave child.

When I reached the house, my mother was walking out of the door and wearing her raincoat to come and get me. She looked shocked and terrified at seeing me. I said, ‘Mummy, look what I have brought for you!’ She immediately pulled me into the house and hugged me; she checked if I was alright, and then slapped me and asked me in Hindi: ‘How could you walk home all by yourself?’ When she stopped shouting, I told her that I could not wait at school any longer; that I wanted to surprise her with the gift, thinking of the joy it would bring her. My mother called the school principal and asked her where I was. After ten minutes of waiting, the embarrassed principal told my mother that I was nowhere to be found, and that she would call the police. The principal was then informed that I had come home, having slipped past school security and made my way alone. The principal was shocked, and apologised profusely.

The following morning, my name was announced at the school assembly, and I was called up to the stage to receive a certificate of bravery. The incident was retold and a speech was given on how it was brave but very dangerous for me or anyone else to walk home alone, and that none of us should ever do it. Everybody clapped for me and that made me proud, but I knew I had got off easy.

Incidents like these have remained etched in my mind. I grew up, made a great career for myself, and got married to the love of my life. We had three children and adopted three more, helped orphans by opening up an orphanage, and engaged in empowerment work. Thus, we lived happily ever after.

But before that, my story took many twists and turns.

***

And we go back to where we came from, unhappy as we are

Happy where we are,

Will time once again come to our rescue . . .

And make us adjust to change all over again?

I should have known that everyone has to play the game called ‘change’. To win it, the strategy is simple: Just accept and endure it. Fools like myself give up and fear it; it is a lesson learnt late. But finally the mist cleared. I want to tell everyone that permanency is a myth.

It was time for us to move back to India. We were upset about having to leave London, but a new chapter awaited us back home. We were in transit accommodation in New Delhi, in an officers’ guest house called Punjab Bhawan. We all lived in just one room with an attached bathroom for one-and-a-half years.

My sister and I were admitted to the Air Force School, and we started to readjust to our culture and country. We were not particularly inclined towards studies, being average students in school. I don’t know whether it was because both Sati and I were not committed students or because of our parents’ marital disharmony.

It was then that I began to see that all was not well in my parents’ marriage. They bickered over everything: From money, to style of living, and, of course, us. Their differences were no longer below the surface, and they could not contain the animosity that simmered in their relationship. Neither of them was completely in the wrong; it was just that they were different from each other. At that age, I began to understand that no two people are the same; all that matters is that we learn to adjust to each other’s quirks and individuality.

Since our parents constantly fought and there was always tension and a hostile environment in the house, Sati and I tried to keep away from all the stress that was building between them. We were close, but we were very different from one another. However, that difference did not affect our relationship in any way. I remember how Sati taught me to ride a bicycle. Every day when we went out in the evening to play, after school and after finishing our homework, she would make me ride the bicycle and hold it from behind so that I didn’t fall. When she let go of the cycle, sometimes I would fall and sometimes I would just keep riding. It gave me so much comfort to know she was right behind me. Soon, I started riding with my friends all around the neighbourhood and to the local market.

I loved Sati so much but I never vocalised my emotions. I knew that these things went without saying and, in our hearts, we would always remain bonded, no matter what. I grew to rely on her and she always protected me, taking care of me. I took advantage of her gentle behaviour whenever I could. When we would receive gifts, I would always pick the best toy first. I don’t know whether she let me get away with such boorish behaviour because I was younger or she just let me win through sheer maturity on her part. She was always the one to sacrifice for me. I was beginning to act spoilt and needed attention all the time, especially from my mother. Sati was the opposite: She was responsible and self-reliant.

After a couple of years, Papa went back to his cadre in Punjab. Now that we were moving to Chandigarh, I wanted to find out the exact nature of his job. He was an officer of the Government of India. He was a cop, and quite an important one. We were given a huge house in Sector 16; even cars, drivers and bodyguards. Initially, when we saw Papa surrounded by gunmen carrying AK 47s, we were astonished. Papa asked my sister: ‘Sungua, how do you feel? What do you think when you see all these bodyguards protecting me and you and Mamma and Bungua?’ ‘I feel that we all have done something wrong and the police are trying to catch us,’ Sati replied, and Papa and Mamma began to laugh, which set us laughing too.

Before we joined school, our names were returned to the original: Sati became Sati Srivastava again, and I became Amrita Srivastava. And our dear Papa became Ram Swarup Srivastava once more.

One evening, Papa was sitting in the garden which my mother had sculpted so beautifully. Mamma was very creative. She could transform a government house into a five star hotel. Papa and Mamma may have had different tastes, but Papa was very proud of Mamma’s decorative skills. He used to call her Neeki, a pet name he gave her. Out of affection, she called him Rishi. Mamma was a big fan of the actor Rishi Kapoor.

That evening, Neeki and Rishi were sitting on the white wrought iron furniture in the garden, enjoying cups of tea. Sati was in the bedroom that we shared, when I ran downstairs to the garden. ‘Papa, I want to talk to you,’ I said. Alarmed, Papa asked: ‘What happened?’

‘Papa, I know what Ram means. Ram is our God, and He is in the Ramayana.’

‘Yes,’ Papa said, sounding curious.

‘What does Karna mean then, what does Sati mean and what does Amrita mean?’

Papa explained to me that evening the meaning and significance of our names, and the stories behind them. He also briefly narrated to me the legends of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, and the characters within them.

A few days later, inquisitive and excited about these great epics, I asked Papa many questions regarding the characters, their significance, and more. He patiently dealt with my queries and enlightened me.

Then he asked, ‘Who do you like in the Ramayana?’

‘That’s easy, Papa. I know you know my answer. Shabri.’

<

br /> He laughed and asked me, ‘Why Shabri?’

‘Because Shabri is a lifelong devotee of Lord Ram, and your name is Ram and I am your devotee, Papa, so my turn to question: Why did you not name me Shabri?’

Papa laughed and said, ‘Because Mamma is a fan of Amrita Pritam and Amrita Shergill, so we named you Amrita.’

My childhood was filled with such innocent thoughts, and my Papa and I shared a very close relationship.

However, my parents’ marriage was clearly falling apart. Papa would stay at work most of the time. He worked till the late hours of the evening, came back home around 9 p.m., and would often skip dinner. Mamma kept herself busy with housework. The sleeping arrangements had changed. Mamma, Sati and I slept in the master bedroom upstairs. Papa slept alone in the room downstairs. Both rooms were cursed in my opinion. The whole house was cursed.

But no matter how terrible their fights got, no matter how horrible their relationship was, I never imagined that they would actually part ways. The thought just didn’t occur to me. I did not know anyone whose parents were divorced; not even in England. I always fantasized a fairy tale ending for Papa and Mamma, ignoring all the signs that theirs was anything but a fairy tale. I always thought that one day, my parents would see how silly all their arguments really were, and they would be reminded of the love they had for one another. The memory I had of them blissfully holding hands in the red-and-yellow tulip gardens of Amsterdam was the picture that remained in my head. Whenever things got bad between them, I wanted to transport them back to those happy days, making them remember the love that they had for one another. As children, we never think of our parents as individuals who also have a life of their own. We think of them only as our parents; people who should be together, no matter what.

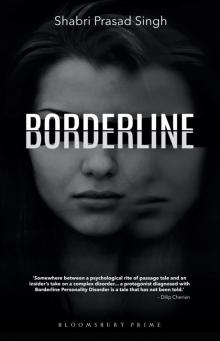

Borderline

Borderline