- Home

- Shabri Prasad Singh

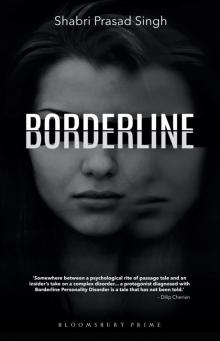

Borderline Page 9

Borderline Read online

Page 9

The cops were under the impression that they had settled the dispute. They were about to leave when one of them asked if I needed to be dropped back to my place. I agreed. I was sad, exhausted, angry, and going through anxiety, and yet I was behaving in a very robotic manner. Just as we were reaching my place, I asked them to stop the car. I couldn’t bear the thought of being alone in the apartment: I thought I might die from anxiety or I might actually kill myself. So instead of dropping me home, I requested the cops to take me to hospital instead. That decision would change the course of my life. However, I did not know this at that point.

Once at the hospital, the cops made me do some paperwork, after which I was taken to see a doctor. I don’t know if he was a psychiatrist or not; I was far too consumed by my conflicting emotions to pay any heed to the details. The doctor asked me some questions, including whether I intended to commit suicide. I told him I didn’t want to, that all I wanted was to speak to Hafez. He made me talk to Hafez on the phone, and was present during the conversation. I went on talking like a broken record, but no one said anything.

When the conversation ended, the doctor said he would have to admit me to the hospital. He said, ‘If you had said “goodbye” to Hafez and were willing to accept that the relationship was over, I would have let you go.’ But because I was still obsessing and emotionally unstable, and capable of harming myself, he had to admit me. He took my sister’s number and that of my parents in India. He told them that I would have to be admitted for the foreseeable future. My family took immediate action and I was booked on the next flight to India, which was to depart the following day.

My corner of the emergency ward was tiny, almost like a prison cell. I was so emotionally and physically exhausted that I kept crying thinking about my father and how he would have protected me if he were still around. I cried over my sorry and pathetic condition, not realising it was I who was responsible for becoming who I was. I asked the doctor to give me something to help me sleep. He gave me an injection of diazepam and slowly my whole body came to a floating state and finally my eyes shut. When I woke up in the morning, Hafez’s mother was there. She had come to pick me up and take me to my house so that I could pack and leave for India. I went home, packed my things, paid my rent and asked Aunty if I could see Hafez one last time. She told me he was going to take me to the airport.

Hubert, my therapist, called. He must have been alerted by the doctor at the hospital as to what had happened. He told me he thought it was a good idea for me to go back to India where I had family and support.

Hafez drove me to the airport. He was warm and friendly, and he held my hand and hugged me. Perhaps even he realised that this was the end of our journey together. I didn’t want to say ‘goodbye’, but I knew I had to. I didn’t know if I would ever see him again, and I didn’t know what was in store for me. All I knew was that if I hadn’t told the cops to take me to the hospital, I would still have been in New York, and would have found a way to make Hafez talk to me.

Only time would tell whether this had been a good thing or bad. But one thing did happen for certain: Because of my obsession, I never could complete my education.

Chapter 13

TRANSFERENCE OF SOME KIND

Human beings have many defense mechanisms to protect

themselves from schisms and emotional embolisms.

After a long time of suffering and pining,

the mind finds distraction which it portrays as charming.

To transfer one’s intense emotions from one person to another

may not be the best thing to do,

But when the mind and soul have had enough,

they plan on changing their point of view.

Was begging for love a crime? If yes, then I was a criminal: A defeated criminal, because no matter how much I begged, the person I loved ran further and further away from me. Over time, one learns that love cannot be forced; its sublime nature demands freedom. But I had not learned this yet.

I was still fixated on Hafez. Even now, after reaching India, after talking for hours with my mother and Uncle about how he was unworthy of me, and how he had mistreated me, I still did not let go. I would get all fired up and call him names after I was made to revisit the instances of ill-treatment, but when I was alone, I would forget everything and pine for him.

My concerned family took me to a well-known psychiatrist, Dr B.S. Wadia. His assistants took down my history and gave me the Rorschach test. It is a test in which subjects or people are shown a variety of inkblot images and then are asked to state what do they make of them or what do they see in them. Then the psychoanalyst giving the test psychologically interprets the answers to judge the persons state of mind. I found it amusing to look at inkblots and describe them. I wondered how on earth these cards could help them analyse my inner turmoil.

I was quiet at the institute, and chills ran down my spine as I felt trapped. It was the same feeling I had in the hospital in New York. I tried to act normal, as though nothing was wrong with me, so that they wouldn’t admit me there. I could see a few in-house patients, some of who were talking to themselves and some were stone cold, almost catatonic, and staring into the emptiness ahead of them.

Then the doctor called me in. He was tall and slightly overweight, and had a salt-and-pepper beard. He was well dressed, soft-spoken, and exuded kindness. He spoke to me gently, and I told him about what had happened—how I had been forced to leave New York because of my love for Hafez. I told him how badly I wanted Hafez back. He listened without interrupting, and then politely asked me to leave so that he could have a chat with Mamma and Uncle.

They came in as I was leaving the room, and the doctor asked me who was this man who was accompanying my mother. I surprised myself by saying, ‘He is my father.’ I had never thought I would address Rana Uncle as my father, but I did call him that. I had begun to accept Uncle—a man of great intelligence, humility and compassion—and I could clearly see that he was a pillar of strength and support for my mother, and now for me.

After the session, when my parents came out of Dr Wadia’s chamber, they seemed to be in a hurry to leave. I don’t know the details of the conversation they had with the doctor, but it seemed to have left them troubled. I was more than pleased to leave, since the place gave me the creeps and I pitied the patients who were living there, lost in their own world. It made me think of my Aunty Mira, and how her condition had become so sad because of her love for a man who could not return her feelings. Was I going in the same direction? Was history about to repeat itself in this family?

On the way back home, my mother told me that the doctor had asked them to admit me in the hospital. Since they knew I wouldn’t want that, they had decided to leave. They told me we could get a second opinion and I said, ‘No more doctors. I will deal with my feelings myself.’ I continued, ‘What the hell was I thinking? I should have just asked the cops to drop me home instead of taking me to the hospital.’

Uncle looked at me and said, ‘You were there for all the wrong reasons. Something like this was bound to happen. You were not studying, simply stalking Hafez. I’m glad that you are back in India with your family. You are not well, and you need treatment and care.’ I didn’t comprehend anything, as my mind was lamenting the loss of Hafez. Or was it actually still lamenting the loss of Papa? What would become of my studies? I asked my parents that question and Uncle answered, ‘We are going to Patna tomorrow, and you will take a break. After that, we will figure out what the next steps will be.’ We were currently in Mumbai but had to go to Patna as Rana Uncle was posted there as Deputy Commissioner.

I kept quiet, deciding to go with the flow and listening to what I was being told to do. I was deeply troubled. Stoic silence was my only defense.

A month went by in Patna and I had gotten used to my routine there. My mother and Uncle were parents now to a baby boy who was born on 1 November 2004, in Mumbai. He was named Anup, but I called him Jerry. Playing with him, holdi

ng him and watching him do his antics took away a lot of my stress. I often told my mother that he reminded me of Jerry from Tom and Jerry as he was small and chubby, with a brown complexion.

After a lot of effort, I somehow convinced my parents to let me go back to New York for the fall semester. I promised them I would not have anything to do with Hafez. ‘All I want to do is graduate,’ I told them. ‘I already have sixty-two credits; another sixty and I’ll graduate. It would be such a pity if all those credits go to waste. So much money has been spent already.’

When my father had passed away, the Chief Minister of Punjab had promised a sum of fifty lakhs for my education in honour of my father’s dedicated service. Uncle arranged a meeting for me with the Chief Minister, and asked me to go to Chandigarh to ask the government to fulfill the promise so that I could go back to continue my studies. I was to stay with my father’s batchmate, Kaushik Uncle. I packed my bags for a week, and left for Chandigarh. I really did not want to go; it was painful for me to go back to the same place where I used to live like a princess, and it had so many memories of my Papa.

I met with the Chief Minister. He told me his assistant would get in touch with me and the money would be given. This never happened. I followed up, but no one put me through to him. I realised this was an empty promise and they were dishonoring my father’s memory and his years of honest service by not giving me the money. I knew how politicians and their promises worked, but I still had to try.

The night before I was supposed to go back to Patna, Kaushik Uncle’s daughter took me to a club called Copper Club. It was a small place with a tiny dance floor next to the DJ’s station. We were hanging out there with her friends. I kept looking at the watch, wanting to go back, when suddenly I saw him.

He was very fair and handsome, with long hair and a stubble that suited him well. I went to the ladies’ room to fix my make-up, and when I came out I bumped into the same handsome guy I had been eyeing. I said ‘hello’ and he greeted me back, and asked me if I knew him. I said, ‘No, but I sure want to.’ He laughed and we flirted for a while. It turned out his father and my Papa were batchmates. His father had been in the 1976 batch of the IAS while my father was in the 1976 batch of the IPS. I told him that my stepfather was also in the Services but was junior to them. He asked about my father and I told him that he was no more.

The more we talked, the more we seemed to have in common. We had many mutual friends; we had even gone to the same high school but had never known each other as we had been in different sections. He, too, knew the pain of losing a parent as he had lost his mother in a car accident when he was two years old. That explained the hidden sadness I saw in his brown eyes. He took me for a walk and then suddenly pulled me closer to him. He touched my face softly and started to kiss me, sending a sweet sensation up and down my body. My heart was fluttering as a result of the passion I was experiencing after so many months.

His told me he wanted everyone to call him by his last name: Gill.

He was the first man I had kissed after Hafez, and I was feeling strange. I told him I was leaving for Patna the following day. He asked, ‘Why don’t you stay back for a couple of days?’ I wanted to, but I couldn’t.

When I got back to Kaushik Uncle’s house, I got a call from Gill at around one in the night. He asked me to sneak out of the house. As I climbed over the barbed wire, I cut myself. It didn’t help matters that I was wearing a very short skirt. As I was jumping over the wall, he caught me and we had a laugh. We went for a drive, and he said he wanted me to stay back and not leave the following day. But I had to go. We spent all night talking and kissing, and to my surprise, I found myself forgetting about Hafez. I was getting my old confidence back, and feeling like myself again, after a long time. I told him I would visit Chandigarh soon and left the next day, feeling lighter than I had in far too long.

Was I transferring my feelings, my crazy obsession, for Hafez onto Gill now? Was this how it was supposed to be?

***

Could it be so easy, that to get over someone,

one must find someone new?

This cannot be the solution but for now it turned out to be true.

The dampness of my past was slowly drying away;

This freshness from someone else was keeping my misery at bay.

Usually, when one is hurt and abandoned, one needs to take time off to heal and sort out one’s life. However, things seemed to be happening quite quickly for me. I wondered whether I was on the rebound, but it didn’t matter. I was desperate to feel good, no matter how it happened. I needed validation, and was willing to go to any lengths to get it. Perhaps subconsciously, I was trying not to become like my Aunty Mira, who had been obsessed with only one man all her life, so much so that she turned crazy. I grabbed the opportunity to let someone else into my life as I had to move on somehow.

When I reached Patna, I told my parents all about my visit to Chandigarh. I told them that I didn’t think the Chief Minister would give me the money he had promised, so I asked them if they could finance the next semester for me. I wanted to graduate as my father and stepfather both had invested a lot of money in my education. At the same time, I was also confused about whether I would actually be able to keep myself from getting distracted by Hafez and focus enough to graduate. Even if I couldn’t become a doctor, I thought, I could graduate as an archaeologist.

Uncle sent the money to my university in good faith. Meanwhile, I told them a little about Gill, and it turned out that Uncle knew his father. They made jokes, saying that he was from a conservative Sikh family which would only accept Sikh girls. I didn’t pay any attention as I had no intention of getting serious with this guy.

I went to extremes to either hate or love a person. I had gone from idolising Haff to detesting him and thinking he was beneath me. I did the same with my mother. There were times when I idolised her and then if she did something I did not like or said something that made me angry, I would demonise her. I had a tendency to see relationships in black and white—there was no room for failure. It could get bad, but it could not end. I had been through my parents’ divorce, but I told myself that I was different. I would go to any length to make my relationships work. That is why I had dragged the dead weight of my relationship with Hafez around for so long.

Gill kept me humoured over the next few weeks by texting and calling regularly. He frequently asked me to come to Chandigarh to see him. We talked a lot and it was nice to get to know him. He told me a lot about himself. Although he had been too young to really know his mother (she had died when he was two years old), he said, ‘I have vague memories of her. I remember her I and I can visualize her face, but in blurred memories only.’ That was the hidden sadness I had seen in his eyes when we first met. He knew what loss was.

One day, my mother fell quite sick, and had to be taken to Mumbai for proper treatment. I told Rana Uncle I would go to Chandigarh and try to push for the money again. I called one of my father’s juniors and asked him to arrange my stay at the government guest house. I was excited to see Gill again.

As I reached, Gill proposed we go to Copper Club, where most of Chandigarh’s young crowd hung out over the weekend. I got ready, looking sexy and elegant at the same time, and Gill picked me up to take me for our night of clubbing. I met a lot of my friends, and had a good time.

It was quite late when he dropped me back at the guest house. He wanted to come up to my room, but I wasn’t ready to have sex with him, even though I was so attracted to him.

We dated casually over the next few days, and one night, he took me out for dinner. He complimented me on my looks, and made me feel special, wanted and appreciated. We went back to his house that night, and for the first time, we made love. He was a good lover, and although he was not well endowed, he was well versed in the art.

That night, I gave my heart away yet again. Hafez became a distant memory, and the era of Gill had begun.

***

Loving someone

who does not love you back—I did not even

know when it became my pattern and a terrible one at that.

Even the outcome of such an obsession is bound to be coloured black.

Unrequited love is a curse and it will always

make one’s soul feel empty,

It is a pointless pursuit, in the end one’s soul will get cracked.

An inner voice kept telling me I shouldn’t go ahead with it, but I did not heed it. Instead, I allowed a terrible pattern to form, once more, for someone who didn’t deserve my love and affection. I understood much later that it could not have been love that I was feeling or fighting for. Rather, it was a dark, paralysing obsession in the guise of love, first for Hafez, and now, Gill.

There were two nightclubs where the who’s who of Chandigarh hung out—Copper Club and Silk Lounge. I told Gill I wanted to go to Copper Club with him, but he said he was busy. I was noticing that he was increasingly becoming elusive. I went to the club with other people I knew, but soon got bored, and I couldn’t stop thinking about Gill. I suggested to the others that we go to Silk Lounge. When we reached there, I saw Gill with a big group. I wanted to confront him, but deciding to act mature, I let it be.

That night, my calls to Gill went unanswered. I was quite upset, wondering whether this relationship was ending even before it had begun. Was it going to be another case like that of Hafez?

I received a call from Gill’s friend, Raj. He said, ‘Amrita, Gill can’t tell you this straight on your face, but he is not ready for a relationship. He is too young for a commitment, and I believe that’s what you are looking for. He just wants to have fun and play the field.’ Gill and I were the same age, our birthdays literally being nine days apart. I took these words to heart and felt rejected all over again. Raj probably sensed my vulnerability, and asked me out on a date. I was furious. I wasn’t some toy these guys could pass around and play with. They probably looked down on me, I thought, since I was living alone in a guest house. They may be assuming that I had no one to look over my shoulder. I could understand their arrogance, as I had been through the same when my father was alive—I lived like a princess, with servants, cars, gunmen all at my beck and call day and night, no one daring to even look my way, forget about touching me . . . However, I now saw all this in vain. In fact, I pitied their narrow point of view. But I underestimated the power of this small town and the way the people of this town were conditioned into thinking. It would be something that I would have to fight later on.

Borderline

Borderline